Gambian lawmakers voted on Monday, July 15, 2024 to uphold a 2015 ban on female genital mutilation (FGM), rejecting a controversial bill seeking to overturn the law after months of heated debate and international pressure.

Legislators killed the bill by voting against all the proposed amendments to the 2015 text that would have decriminalized the practice. “The Women’s (Amendment) Bill 2024, having gone through the consideration stage with all the clauses voted down, is hereby deemed rejected,” said Fabakary Tombong Jatta, the speaker of the National Assembly. “I rule that the bill is rejected and the legislative process exhausted.”

The bill had been making its way through parliament since March, deeply dividing public opinion in the Muslim-majority West African country. The text, introduced by MP Almameh Gibba, argues that “female circumcision” is a deep-rooted cultural and religious practice. However, anti-FGM campaigners and international rights groups contend that it is a harmful violation against women and girls.

FGM involves the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs and can lead to serious health problems, including infections, bleeding, infertility, and complications in childbirth. According to 2024 figures from UNICEF, The Gambia is among the 10 countries with the highest rates of FGM, with 73 percent of women and girls aged 15 to 49 having undergone the procedure. A UN report from March stated that more than 230 million girls and women worldwide are survivors of the practice.

“This vote is a significant victory for women and girls in The Gambia,” said Divya Srinivasan from women’s rights NGO Equality Now. “We hope this sets an example in the immediate region as well as in the whole continent.”

Amnesty International also welcomed the decision to uphold the 2015 ban. “In 2015, the adoption of the Women’s (Amendment) Act, which criminalizes and sets out punishments for performing, aiding, and abetting the practice of FGM, represented a significant milestone in the country’s efforts to safeguard girls’ and women’s rights,” said Samira Daoud, Amnesty International Regional Director for West and Central Africa. “It was essential that this progress was protected.”

However, Amnesty International stressed that the government must do more to uphold the law and address the “root causes of the issue to change attitudes and norms in order to empower women and girls.”

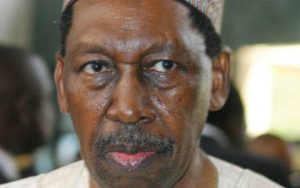

Former Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh, now in exile, banned FGM in 2015, branding it outdated and not a requirement of Islam. Parliament later that year adopted the first law specifically banning the practice, which is now punishable by up to three years in prison. However, in reality, FGM has not been eradicated in The Gambia, with the first convictions for performing the procedure only taking place last year.

The convictions sparked the issue, leading Gambian legislators to refer the Women’s (Amendment) Bill 2024 to a parliamentary committee in March. Last week, lawmakers backed the committee’s conclusions calling for the ban to be maintained. The report from the joint committee on health and gender stated that repealing the ban “would expose women and girls to severe health risks and violate their right to physical and mental well-being.” It also noted that consultations with Islamic scholars confirmed that the practice is not a requirement of Islam, an argument commonly used by FGM advocates.